Jim McGreevey is well versed in the notion of reentry. His personal life and career seem to map out in a schematic of turns, reverses and junctions that eventually propel him forward in one direction or another. A former governor of New Jersey, he resigned his position in 2004 two years into his term after a personal scandal rocked his administration. Years later he chose a completely different path by seeking to become an Episcopal priest and obtaining a Master of Divinity degree from General Theological Seminary in New York City only to see that road blocked when the Episcopal Church declined to ordain him. McGreevey, nonetheless, continued to pursue his interest in ministering to inmates and enlarging opportunities for these individuals to successfully negotiate their own reenter into society after their release. This work resulted in McGreevey being appointed chairman of the board for The New Jersey Reentry Corporation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping inmates successfully return to their communities after their release.

His current focus and ongoing passion remains creating a reliable and structured pathway for prison inmates to successfully rebuild their lives, engage their communities and stay out of prison. Essentially, to reenter wider society as a productive member. He argues forcefully that reworking our approach to incarceration and rehabilitation is critical to this process. It not only benefits inmates looking to rebuild their lives, it provides sizeable financial and societal returns to local communities and state and federal jurisdictions.

McGreevey laid out his vision to WellWell recently in an extended discussion that covered prison reform, inmate reentry and the potential personal and financial costs that’ll continue if the current system remains unchanged.

This is the first of WellWell’s two-part interview with Jim McGreevey.

Can we start with an overview on the scope of New Jersey Reentry Corp.?

Absolutely. We have 8 sites and 700 clients in the state of New Jersey. There’s a significant conflation between imprisonment and addiction so that if you’re to look at our population, upwards of 78 percent are acutely addicted. In addition, upwards of 40 percent have Hepatitis C, as well as 40 percent that struggle with mental illness. It’s a population that struggles across a number of different territories whether it’s mental illness, medical illness or addiction, and that is why we have such a strong focus on the medical and behavioral approach to addiction treatment.

Your group claims it costs $53,000 to incarcerate someone. Do you think there is a better way to spend that money, particularly for someone who may be in jail largely due to issues related to addiction or mental health?

That’s an excellent question. I think that New Jersey, as well as a majority of states, have long grappled with the dilemma of institutionalization, tracing back to how mental health was handled in the 1960s and 70s. Largely, there was a well-intentioned but unfulfilled commitment to provide for deinstitutionalization and then subsequently, community-based support for mental health in terms of psychiatric and psychological access, pharmacology and housing environments that would be conducive towards persons confronting mental illness. Unfortunately, we only did the first part. We deinstitutionalized, which was roundly applauded. But ignored the other steps and issues. At the end of the long day for so many individuals in New Jersey, the sad legacy was moving into boarding homes, sometimes with squalid circumstances, all over the state. And so those that were mentally ill moved from large scale state institutions to single room occupancy, hotels and rental assistance properties whose living conditions were often less than adequate.

Certainly, they did not have anywhere near the level of medical and behavioral support that was originally envisioned and many candidly died. And for many it led to a descent into addiction, which was seen in the rise of crack cocaine use in the 1980’s or the continued rise of opioid, heroine and fentanyl from the 90’s to the present day.

U.S. incarceration rates have reportedly grown eightfold since 1970 while crime has actually decreased. What is it about the current system that we have right now that is causing this disparity?

I think there are a number of reasons. Noted criminologists at Harvard, Yale, and Columbia point to various drivers, including racial bias or a reaction to the drug laws that were commonly referred to in the New York region as the Rockefeller Laws. And also, sadly, there’s the trajectory of new felonies being created. From pre-colonial times through World War 2, there was a relatively incremental increase in the number of new felonies that were enacted. But in the aftermath World War 2, whether because of or in response to civil rights or the drug crisis, there was almost an exponential increase in the number of new felonies that were being created by state legislators and Congress.

Concurrently, there was the “get tough on crime” movement with new three-strike mandates, which created presumptive terms. State by state largely removed the discretion of judges to sentence in accordance with unique circumstances. So, with the advent of more felonies, longer terms and removing the discretion of judges as to issuing sentences, the U.S. prison population inexorably bloomed.

What role does the increase in private prisons over the last few decades play in this?

So, right now in America, I believe one out of every 32 Americans is in a state prison, federal prison, county jail, county probation or state parole. One out of every 32, it’s an awful number. We have more of our fellow citizens incarcerated as a percentage of the population than any nation in the world and concomitant with that reality is the financial incentive of the private sector to build and maintain prisons at full capacity. You see private prisons in the form of both federal and state prisons, halfway houses and various detention centers everywhere and they have become profit centers.

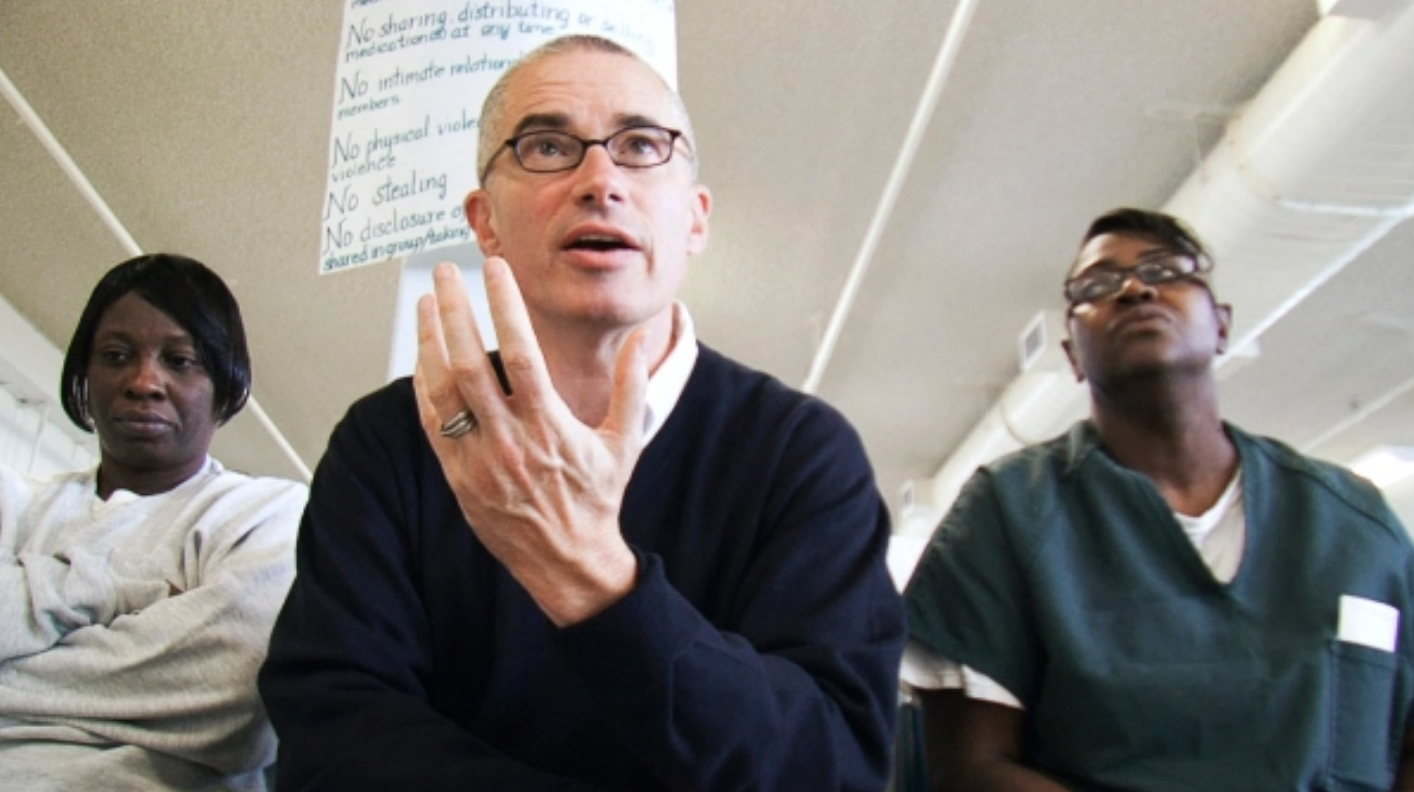

(photo source: Instagram @nj_reentry)

What is the solution or alternative to rising prison populations and their associated costs?

We’re in the business of reentry, so we’re in the business of people walking out and not going back to prison. We make the argument that if 97 percent of persons being released are coming home, well then, we better want them to be successfully reintroduced into society for all sorts of reason. Hopefully, our stats bear truth to the fact that a successful reentry is possible. Only 8.8 percent of our participants are reincarcerated. They have a 19.7 re-arrest rate. People can be re-arrested for technical violations, but those being reincarcerated is less than 10 percent.

You can contrast that with national numbers that are 6, sometimes 7 times higher. We do the hard work of securing medical assistance, behavioral assistance and particularly addiction treatment. We emphasize medication assisted treatment for those that are active in their addiction with heroin or fentanyl, providing access to a federally qualified health center and Medicaid. Then we work diligently with training, skill-based training and employment, housing and legal services so it’s a somewhat comprehensive array.

Imagine what it would be like to drop anyone into the middle of any New Jersey community without an ID, without a driver’s license, without healthcare, without employment, without housing. You would just struggle to survive. If we don’t provide these threshold basic services to ensure that someone has the ability to maintain themselves in a safe and secure space, with access to basic food and access to training with the prospect of a job, people are going to just run, gun and dope. So, that’s our argument.

I’d also make the argument that prisons don’t work. For example, in the state of New Jersey where I think both the state legislature and the governor’s offices have done a tremendous job in supporting reentry, the prison budget is still over $1.6 billion. You look nationally, it’s even worse. So much is spent in this country on incarceration. The reality is that if you look at countries that are more progressive, such as Scandinavia, they’re training and teaching people how to actually come back into society and be successful citizens. I would argue that we still have a British colonial model that the British no longer even employ in the sense that it’s a binary model, you’re either guilty or you’re innocent in terms of our justice system and if you’re guilty, you’re put in prison. Prison is seen as something punitive, but nobody comes out of prison better off in this country. Nobody comes from prison psychologically healthier.

So, the issue is systematic?

Our system isn’t designed to help people reenter society. There’s a whole movement among certain policy makers that say there are those few very bad people, evil malevolent people, who should be in prison forever. In reality, people are rarely pure evil. But that’s not how we decided to punish people in America. Instead, we use those evil people as the rule rather than the expectation all too frequently and have for a long period of time.

We don’t discern between people who should be there ostensibly for a long time, if not, forever and those who should be out in a much shorter timeframe. Certain countries focus on this. They understand that at the end of this process, people are coming home. This then begs the question: are prisons instructing or changing behaviors to help these people to make the transition to become responsible and healthy members of civic society or just setting them up to go back?

A lot people don’t realize that 95% of the people in prison will be eventually released. Then you’re probably also confronting the notion of “Well, they’re criminals. They’ve made their bed.” While this may seem initially understandable, it seems counterproductive to those being released and to society as a whole.

So, this often lends to a discussion on criminology and criminal justice from an ethical perspective, even economical perspective. But I think the more interesting angle is from a cognitive behavioral perspective. If you look at the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget and other renowned psychologists, they’ll say there’s a moral ascendancy. That there’s a development of a moral framework that most people engage on, if provided the opportunity. They state that people learn to develop these behavioral patterns premised upon good role models, their social environment, expectations, etc.

So, the dilemma is if we have a 17 or 18-year-old youth, who is consistently participating in controlled dangerous substances, narcotics, either in terms of use or selling, how is placing that person into a state prison going to help. Will it make them aware of the toxic aspects of engaging in addiction and selling drugs, will it help them understand how to change their behavior, will they be in a community that embraces healthy and responsible behaviors? I mean, it’s possible in a state prison but it’s highly unlikely.

In your 2013 documentary, Fall To Grace, the last line is “No one is beyond redemption. No one should be judged by their lowest moment.” How much does your time as governor and how it ended impact your work now for The New Jersey Reentry Corporation?

Tremendously. Being at the top of the food chain, as it were, being in the political class and coming out, accepting my sexuality, then recognizing the precipitous fall. By the way, it’s a remarkable testament to American resiliency and decency how far we’ve come in such a short period of time. I mean, for young Jimmy McGreevey, riding his bicycle in Jersey City or Carteret when he was five, six, seven years of age, frightened beyond belief that anybody would be able to discern that I was gay. Homosexual was barely a real word then. I didn’t even understand what it meant. We’re now in such a different place. For example, look at Pete Buttigieg, he was a viable national contender for the presidency. It’s great. For me personally, it’s about understanding our better angels. An old priest said to me, “the cracks in the vase are where God’s grace comes through.” It’s in our humanity. There’s a great book called The Spirituality of Imperfection. It looks to the desert fathers, the ancient Greek Orthodox, the Hasidic Rabbis, to basically show that we’re all woefully imperfect creatures. Whether you’re a deist, or whether you’re not ascribed to any religion, I think most people recognize their lack of perfection. When you realize your imperfections, the question then becomes, on a behavioral perspective, how do we deal with this crisis in our lives?

For me, it started after college and after law school. I was an assistant prosecutor and I looked at addiction as a moral failing. It was something that people knew was wrong, but they chose to do regardless. Then when I was working with the women in the Hudson County Jail. There was this exceptional young woman. She was bi-racial, and that fact is only important because she was taunted by both sides of the community. She grew up in Camden and her mother used to send her out to sell drugs and make money as a means of paying the electric bill. She was tragically and viciously sexually assaulted, repeatedly, by the time she was 14 in an almost heinous, hellish circumstance. And I remember when she told me, one time she came home and she was literally scrubbing herself, trying to scrub the stain away, the sexual assault while her mother was yelling and cussing at her telling her to get back out there. I’ll never forget, she said to me: “Jim, that’s the last time I’ve ever cried. Life was so bloody hard and difficult.” Drugs became a way to candidly anesthetize her pain. She didn’t engage with drugs for the purposes of pleasure, just her life was so damn ugly and hard and unforgiving and joyless. So, then I began to sort of understand that for many, particularly in public housing, the economies of the addiction or the market of addiction is the only free market available. People aren’t selling all the goods that they would in any given retail mall in New Jersey, it’s a market economy born largely on the backs of addiction and addiction use.

I really didn’t understand this until after I left the governor’s office and after seminary. It came after just listening to people over long periods of time as to why they’ve used and every reason is unique and different. But again, and again, particularly among the poor and the marginalized and people that had survived the chaos in the street, addiction’s a means of escape that I, from my wonderfully middle-class family vantage point, could never understand.

(photo source: Wikipedia)

About Jim McGreevey

Jim McGreevey is the chairman of the board for New Jersey Reentry Corp., a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping inmates successfully return to their communities after their release. A former governor of New Jersey, McGreevey has held a wide variety of elected offices and positions with nonprofit groups.

To learn more visit www.njreentry.org