By John Salak –

The keto diet seems to just love controversy—both to promote its potential benefits and warn against lurking risks. This push-and-pull was on full display recently in studies released by The University of Texas and the University of Notre Dame.

Texan researchers warned that some keto dieters may be at increased risk of damaging heart and kidney functions, while research out of Notre Dame suggested that components of a keto diet in conjunction with immunotherapy may reduce prostate cancer.

Not surprisingly, more work may be needed to prove either or both sets of findings. However, each research project provides some intriguing and possibly alarming considerations.

The University of Texas team, for example, warned that a strict “keto-friendly” diet may come with risks for certain individuals on certain types of keto diets. The group specifically reported that a continuous long-term ketogenic diet may induce senescence or aged cells in normal tissues. This could impact heart and kidney functions. However, the researchers also noted that an intermittent ketogenic diet, with a planned keto vacation or break, doesn’t seem to increase the risk of pro-inflammatory effects due to aged cells.

“To put this in perspective, 13 million Americans use a ketogenic diet, and we are saying that you need to take breaks from this diet or there could be long-term consequences,” said Dr. David Gius, assistant dean of research with the Department of Radiation Oncology at the university’s medical school.

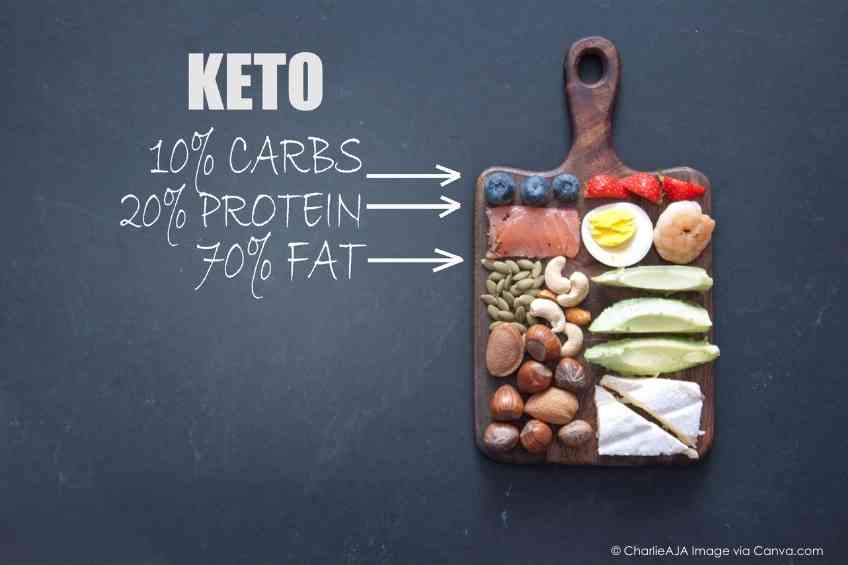

A ketogenic diet, popularly known as keto-friendly, is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet that leads to the generation of ketones. They are a type of chemical that the liver produces when it breaks down fats. The Texas researchers explained that while a ketogenic diet improves certain health conditions and is popular for weight loss, pro-inflammatory effects have also been tied to the diet.

The university’s study showed that at least when it comes to mice, two different ketogenic diets, applied at different ages, induce cellular senescence in multiple organs, including the heart and kidney. However, this cellular senescence was eliminated by a senolytic, or a class of small molecules that can destroy senescence cells and prevented by the administration of an intermittent ketogenic diet regimen.

“As cellular senescence has been implicated in the pathology of organ disease, our results have important clinical implications for understanding the use of a ketogenic diet,” Gius said. “As with other nutrient interventions, you need to take a keto break.”

Research out of Notre Dame examined a different issue when it comes to keto-friendly diets. The South Bend team reported that adding a pre-ketone supplement—a component of a high-fat, low-carb ketogenic diet—to a type of cancer therapy in a laboratory setting was highly effective for treating prostate cancer.

The study aimed at tackling a problem oncologists have long battled, which has put men at particular risk. Prostate cancer is resistant to a type of immunotherapy called immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy. ICB therapy blocks certain proteins from binding with other proteins and paves the way for our body’s fighter cells, T cells, to kill the cancer.

“Prostate cancer is the most common cancer for American men, and immunotherapy has been really influential in some other cancers, like melanoma or lung cancer, but it hasn’t been working almost at all for prostate cancer,” said Xin Lu, an associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences.

Adding a dietary supplement related to the keto approach might overcome this resistance, added lead author Sean Murphy, a doctoral student. Recognizing that cancer cells feed off sugar, the team explored the approach by depriving mouse models of carbohydrates—a key component of the keto diet—in hopes of preventing cancer growth.

Murphy specifically divided the models into six different groups: immunotherapy alone, ketogenic diet alone, a pre-ketone supplement alone, the ketogenic diet with immunotherapy, the supplement with immunotherapy, and the control group. While the immunotherapy alone had almost no effect on the tumors, both the ketogenic diet with the immunotherapy and the pre-ketone supplement with the immunotherapy reduced the cancer and extended the lives of the mouse models.

Ultimately, the supplement with the immunotherapy worked best.

“It turned out this combination worked really well,” Lu said. “It made the tumor become very sensitive to the immunotherapy, with 23 percent of the mice cured—they were tumor-free; in the rest, the tumors were shrinking really dramatically.”

The results point to the possibility that a supplement providing ketones, which are what is produced in the body when people eat a keto diet, might prevent the prostate cancer cells from being resistant to immunotherapy. This may lead to future clinical studies that examine how ketogenic diets or keto supplements could enhance cancer therapy.

The successful impact of the experiment is not, however, because of the lack of carbohydrates in the keto diet. Rather, Murphy and Lu stressed it is about the presence of the ketone body, a substance produced by the liver and used as an energy source when glucose is not available. The ketones disrupt the cycle of the cancer cells, allowing the T cells to do their job to destroy them.

The university’s work may also lead to other disease-fighting advances. “With the main ketone body depleting neutrophils, it opens the door for investigating the effects of the keto diet and the ketone supplement on diseases ranging from inflammatory bowel disease to arthritis,” Murphy reported.