John Salak –

It may seem obvious that good sleep usually depends on a dark room—and it does. There are other critically important reasons to cut out as much light as possible when drifting off. Moderate exposure to light while sleeping can undermine heart health and increase insulin resistance, according to a study by Chicago’s Northwestern University.

“The results from this study demonstrate that just a single night of exposure to moderate room lighting during sleep can impair glucose and cardiovascular regulation, which are risk factors for heart disease, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome,” warned the study’s senior author, Dr. Phyllis Zee, chief of sleep medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “It’s important for people to avoid or minimize the amount of light exposure during sleep.”

The impact of light during the day has already resulted in increased heart rate via activation of the sympathetic nervous system, effectively kicking a person’s heart into high gear and heightening alertness to meet daily challenges. Research at Northwestern indicates light has the same effect while someone is asleep, without challenges, inhibiting the body’s ability to rest properly.

“We showed your heart rate increases when you sleep in a moderately lit room,” reported Dr. Daniela Grimaldi, a co-first author of the study. “Even though you are asleep, your autonomic nervous system is activated. That’s bad. Usually, your heart rate together with other cardiovascular parameters is lower at night and higher during the day.”

Insufficient rest isn’t the only drawback to bedtime light exposure. Insulin resistance occurred the morning after people slept in a room exposed to light. The results mean that cells no longer respond well to insulin, and don’t use glucose in the blood for energy, causing the pancreas makes more insulin. This can result in a dangerous build-up in blood sugar, leading to diabetes and obesity.

“Now we are showing a mechanism that might be fundamental to explain why this happens,” Zee said, “We show it’s affecting your ability to regulate glucose.”

Northwestern’s work is important because exposure to artificial light during sleep is unavoidable for many, particularly in large urban areas. The university’s study noted that up to 40 percent of U.S. adults sleep with some light exposure from lamps to televisions.

“In addition to sleep, nutrition, and exercise, light exposure during the daytime is an important factor for health. During the night, we show that even modest intensity of light can impair measures of heart and endocrine health,” Zee added.

Fortunately, the team’s warning also comes with some advice for avoiding the consequence of light exposure. The first suggestion is obvious; don’t turn on lights, unless it is for safety. Make it dim and at floor level. The color also matters. Red and orange lights are less stimulating for the brain, while blue or white light is a pure no-go. Blackout shade or eye masks are also a way to eliminate outdoor lighting creeping into sleeping areas.

If turning off the lights doesn’t lead to better, healthier sleep, perhaps a new wearable device out of Switzerland might help.

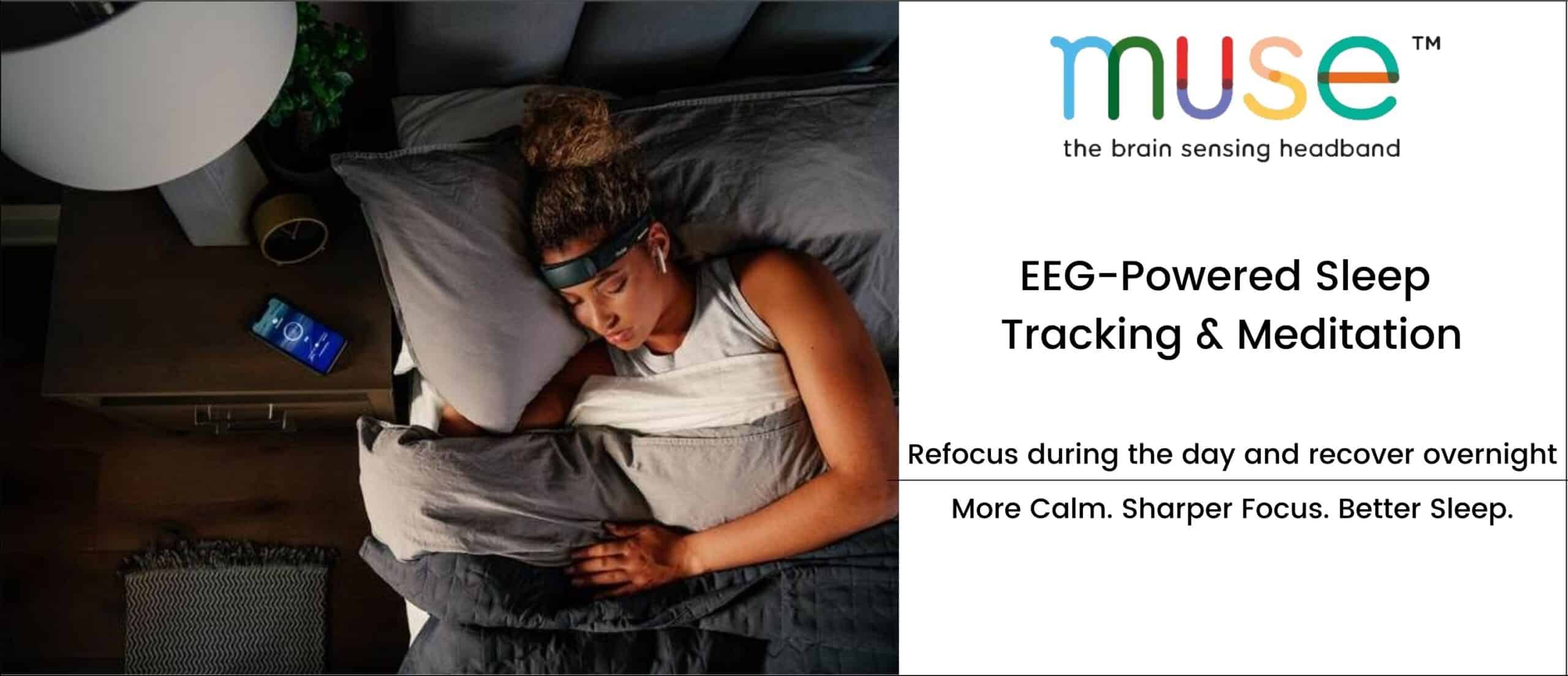

The SleepLoop project has developed a headband that plays specific sounds designed to enhance deep sleep. The good news is that initial trials show the device is effective, but not to the same degree for all wearers.

The project is trying to tie into existing research that shows so-called deep sleep slow waves can be improved by playing precisely timed sounds through earphones while an individual is sleeping. Researchers have seen this process work well in laboratories under controlled conditions but haven’t been able to effectively replicate the impact at someone’s home.

A team at ETH Zurich supported the research by developing a mobile system—a headband with electrodes and a microchip—that can be used at home to promote deep sleep through auditory brain stimulation.

The results have been encouraging but mixed, making any commercial or widespread medical application of the headband a way off. Something researchers and potential users need to sleep on for now.